"6% of adults in this zip code have HIV (not just gays)," and other fun things I've learned from cold-hearted doctors

I have a thing for doctors.

I’m drawn to them, for reasons I’ll never understand.

Perhaps in a past life I was a WWII nurse who fell in love with a hot army surgeon, or maybe I was a patient in a psych ward where the only person that was kind to me was the psychiatrist who did my weekly Rorschach test.

My cousin Sarah does those tests. Well, not exactly those, but similar ones. She works in an inpatient psych ward at a hospital. Last week she and I were at an island-themed bar in Delray Beach, Florida. We were catching up,

“Well, figuring out who we take into our ward is pretty simple,” she began. “We follow the three rules of Jesus.”

“Okay,” I said.

“One — you THINK that you, or others, are Jesus. So you’re delusional,” she said. “Two — you want other people to SEE Jesus. So you’re dangerous,” she continued. “Or three, you, PERSONALLY, would like to see Jesus, so, you’re suicidal.” She took a sip of her key lime margarita.

I’ve always liked conversations like these. I do my best to sit in them as long as possible, relishing in every detail of someone else’s emotionally heightened human experience — as if it were trauma porn.

Being new to Florida, I’ve built a community from scratch and already a few of my friends are doctors.

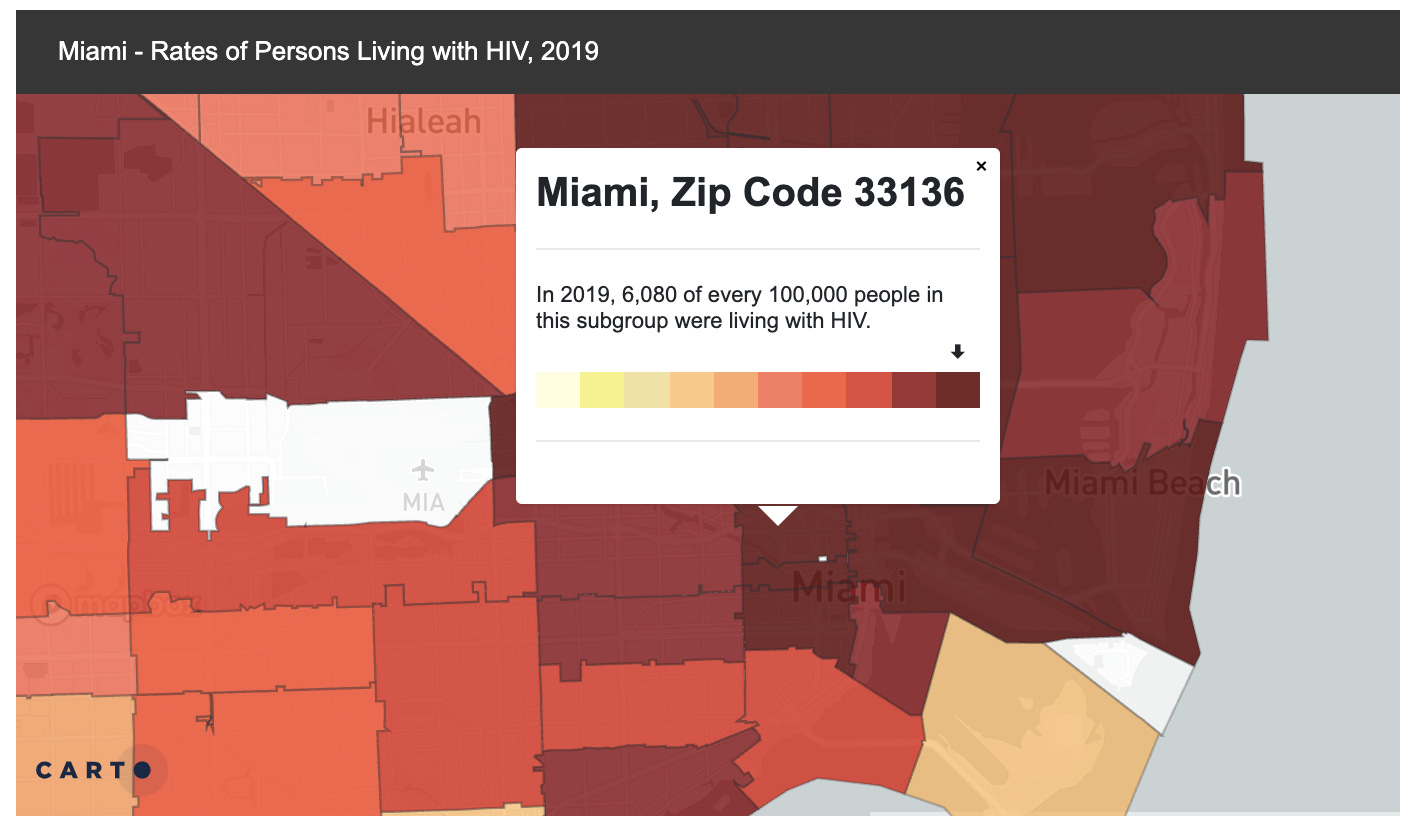

“Well, I thought working at the HIV clinic was gonna be rough, but it was fine,” said New Friend Jack while he watched the TV above the bar. Something with sports. “Yeah. 6% of adults in this Zip Code have HIV,” he said.

“What?” I said. “That’s insanely high.”

“Yeah. But people usually don’t die fast. It’s honestly repetitive. Oh, except for transplant patients. Those are tricky,” he said, still staring at the game.

“Why tricky?” I asked, hoping to get my fix of a sob story.

“HIV messes up your immune system. And when you get a new organ, you always run the risk of infection and there’s a chance that your body won’t accept the foreign organ. So, more infection risk to an already weakened immune system combined with a whole bunch of other risk factors and drugs — basically, there’s just a bunch more ways you can die.”

“Whoa. Have you ever had to tell someone that they’re going to die?” I asked, readying for the juice.

“I mean. Yeah. Obviously.” He scoffed. “Last week, I told four people that they had a year or so left. One of them only spoke Spanish which was hard cuz my Spanish isn’t that good.”

“Was that sad?” I asked.

“Nah. And I really like doing the convos cuz it helps me improve my Spanish,” he said. “Last week I learned ‘letal’, which means lethal, which was so funny cuz before I kept saying ‘letalo’, which means I stalk him.”

Perhaps Jack and I won’t ever be that close. Something about him not giving me what I need. Not allowing me to be a cuck in the soap opera of the tragedy he refuses to feel.

But I wonder if Jack actually does feel it, all the sadness, but because it’s too hard to acknowledge, he pushes it away.

I think my cousin Sarah might be this way too.

“Um,” she said to me, at the beach bar, “When people are at their lowest lows, I like being there.”

“Yeah. I imagine it feels good to be there for people,” I said, picking up a french fry.

“Oh no no no,” she corrected. “I know it came out that way, but no. I just like being part of it,” she said. “I don’t need to be the person you cry to — though I can be, I mean...it’s fine, whatever. I just like being around people when they’re at rock bottom. It’s...interesting.”

She looked past me for a second, and then her face lit up. “Oh my God, but get this,” she paused to make sure she had me. “The other day, this guy came in after having a three-hour suicide standoff with the cops, and they took his gun. Then, when he and I were debriefing, I was like…‘So…is there anything you can point to that pushed you to this point?’”

My knee bounced with excitement.

“He then tells me that he was molested by his dad when he was a kid and now that his dad is getting Alzheimer's his dad doesn’t remember any of it. ‘What do I do with all this stuff — the stuff, that if I ever get the courage to confront my dad about, he legitimately won’t remember?’” She paused again. “Which like, I get, you know? It’d suck to get molested and then be gaslit about it.”

I was pleased to have my story for the day. A disturbing tale worth remembering. And now, as I compare my interactions with Sarah to those with Aspirationally-Spanish-Speaking-Jack, part of me thinks that the two of them might be the same — cut off and walled up, working in healthcare because it’s a place where the apathetic can thrive. The only difference between Sarah and Jack is that Sarah should be on stage.

But there has to be another way — one where you can help others and still feel. Though throughout my years, I’ve never met a physician who I would describe as “warm” — never found a Patch Adams. The closest I’ve ever gotten is my friend Rico who works in the ER.

“I hate when someone comes to the ER alive,” he said. “Because even if there’s nothing we could have done, it’s my fault if they die. So yeah. It’s better when they come in dead.”

“Does it ever get to you?” I asked.

“Well, the other day, this woman came in — she was in her late thirties and had a history of heart failure. She looked at me and said, ‘Doc, I’m scared. Am I gonna die?’ And I looked her right in the eyes and I said ‘No. You’ll be okay.’” He took a sip of his beer and looked off in the distance. His eyes watered a bit.

Five or so seconds passed.

“Then she died,” he said, choked up. “And I wish. I wish I knew how to forget those.”

I, myself, used to work for a funeral company, where we chatted with people whose loved ones were about to pass. But that’s different. Their sadness, the sadness we all feel when we’re about to lose someone, hits differently than the fear we feel when we think that we, ourselves, are dying. That question we ask of “what does it look like for me to fade into the abyss?”. I don’t know if I could sit with someone in that.

I’ve thought about volunteering for a hospice to find out. To see if I’d end up numb, like Jack and Sarah, or tortured, like Rico. There’s probably some other option. Where, the more love you give to others, the more your heart grows. But I think that for most people, true compassion fades as the pain of marinating in others’ suffering becomes too much to bear.

Rico won’t last in the ER. I give him another couple of years before he quits and moves into something like family medicine. Or maybe joins a medical device startup, like high-speed intubation devices, or something much lower stakes like the handheld erectile dysfunction pump he told me about. A lifeline out of the misery that he’s too empathetic to ignore.

Back at that beach bar with cousin Sarah,

“So anyway,” she said, continuing her story about the guy who tried to shoot himself, “I’m sitting with him after a day or so in the ward and I’m filling out his discharge paperwork and he goes, ‘Let me know when I can get my gun back — ideally today’. And then I walked to my supervisor and she says, ‘Just write, Patient requests gun to be returned. And I was like, ‘but what if he tries to kill himself again?’ and she laughed and went ‘oh, sweetie, I hope he doesn’t, but under Florida law, only you can decide if your gun rights are taken away’.”

And then Sarah laughed too.

“But,” I began, “what if he still wants to kill himself?”.

“Well then,” she paused and smiled. “Thank god he’ll have his gun.”

—

My next piece will be about doing Ayahuasca.

It sucked.

Subscribe if you want me to send it along.